On September 18, voters in Scotland will be asked in a referendum whether they want the nation to become independent from the rest of the United Kingdom. The official alliance with England was established in 1707, a union which to date has been contested vehemently by Scot loyalists, represented by the SNP (Scottish Nationalist Party) who will probably be first in line to vote a resounding “Aye”.

Should Scotland secure its independence from England every single facet of the nation as an existing society and as a new, independent country will be impacted – and of foremost interest is the economy.

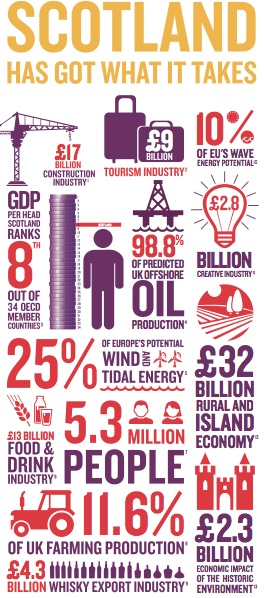

The current Scottish economy is based on offshore oil production, heavy industry, light manufacturing, electronics, tourism, financial services and a vibrant public sector which provides sustainable jobs – but the long-term growth rate has lagged behind the UK as a whole.

Scotland in Numbers

Early in 2013, the Scottish Government and its First Minister Alex Salmond asked a group of prominent economists - The Fiscal Commission Working Group - to produce a report on the design of a macroeconomic framework for an independent Scotland. The group reported: “By international standards Scotland is a wealthy and productive country. There is no doubt that [it] has the potential to be a successful independent nation.”

The group went as far as to add that Scotland is in a stronger fiscal position than the UK as a whole over the last five years to the tune of £12.6 billion. But, in relation to long-term growth drivers of growth and business development, Scotland is still in the rear.

Salmond claims the fault lies with Westminster, namely: an oil fund for future generations hasn't been established (ergo, a substantial GDP), the UK’s massive boom in credit and debt expansion has proved to be anything but stable, UK household indebtedness has increased from 103 percent of gross disposable income in 1996 to 176 percent in 2007, England’s South East has been prioritized economically and the decisions to cut capital spending and impose a policy of austerity on Scotland are, in the words of former Chancellor Alistair Darling, causing “immeasurable damage” to the economy.

First Minister of Scotland, Alex Slamond

According to John Swinney, MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Finance, Employment and Sustainable Growth, a self-governing Scotland will finally be able to attract international investment, create jobs and a more supportive and competitive business environment with its newly established range of fresh policies.

But there could be some very daunting setbacks in store. Scotland would lose its Westminster granted support: Scottish people receive an estimated annual subsidy of £10,212 from the UK government per capita, and its loss would put an end to substantial spending, education grants, public transport and health care. UK debt levels would be shared on a per capita or GDP level, leaving Scotland with a national debt of £80bn - and then some.

With lower crisis reserves, a small, independent Scotland will struggle to raise bail to recue its banks. Also, if Scotland wishes to join the EU, all of the special deals Scottish families benefit from as part of the UK would be put at risk, such as rebates worth £135 a year for every household and opt-outs on the euro.

And high on this frenzied agenda is the currency conundrum.

Scottish Unicorns - Scotland’s original currency (15th Century)

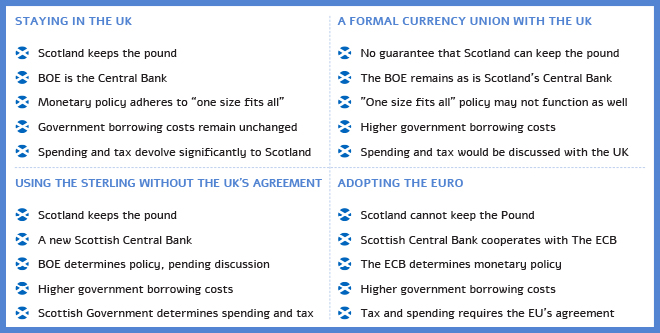

The Fiscal Commission initially examined four currency options, although the ingenuity of analysts in the midst of this conundrum is very inspired, leading to headlines such as “Does Salmond Have a Currency Plan F?" etc.

The key options are: staying with the United Kingdom; a formal currency union with the UK; using the sterling without the UK’s agreement (or under its new term: “Sterlingisation”) and the adoption of the euro and the creation of a Scottish currency. The meaning of each alternative is played out as follows:

The Bewilderment of Consensus

In its analysis, the Fiscal Commission basically concluded that if “it ain’t broke – don’t fix it” - that retaining a formal sterling union with the UK is the top option. Westminster, on its part states that Scotland will still be able to maintain a large banking sector, operating in Scotland and overseas, and that there is a single UK structure for addressing financial stability risks.

There is, of course, the matter of establishing public confidence, which is veering dangerously close to a NO vote according to the YouGov poll, in which 51% voted against an independent Scotland, and 11% remained undecided. Alex Salmond himself lost a TV debate against Chancellor Alistair Darling only earlier this month.

The YouGov opinion poll found that 45% back a currency union, 23% want a separate Scottish currency, 6% support the euro and 8% back a sterlingisation model. But even some of the major leaders opposing Scotland’s independence admit to its capability. England’s Prime Minister, David Cameron, has said: “Supporters of independence will always be able to cite examples of small, independent and thriving economies across Europe such as Finland, Switzerland and Norway. It would be wrong to suggest that Scotland could not be another such successful, independent country.”

To recap, it seems that public sentiment in the United Kingdom - or what historian Simon Schama calls “a splendid mess of a union" - has every right to be confused, but such is the wonder of consensus.