The capture and arrest of the sitting Venezuelan president, Nicolas Maduro, on 3 January has created a stir in global politics, especially around international law. However, another area that has drawn attention is Venezuela’s massive oil reserve.

World’s Largest Oil Reserve Is Now Under US Control

Although US President Donald Trump stated that his country will take over Venezuela’s oil reserve, experts pointed out the details behind the country’s vast oil reserve – and the key word here is “reserve.”

Read the impact of the Venezuela situation on the markets: Why Oil Prices Are Falling? Brent and WTI Slip after Maduro Capture in Venezuela as Gold Surges

Venezuela is sitting on the world’s largest proven oil reserves, exceeding 300 billion barrels, Arne Lohmann Rasmussen, Chief Analyst and Head of Research at Global Risk Management, pointed out. However, the country is currently producing only around 1 million barrels per day.

He further noted that production has been rising over the past five years after falling below half a million barrels per day in 2020, when oil prices collapsed. Even so, output remains well below levels seen 20 to 25 years ago, when production was around 2.5 million barrels per day.

Despite sanctions, Venezuela continues to export roughly half of its oil production. The US company Chevron is also a major producer in the country.

Related: Venezuela Crisis Turns Crypto into a Global Market of Last Resort, Exposing New Risk for Brokers

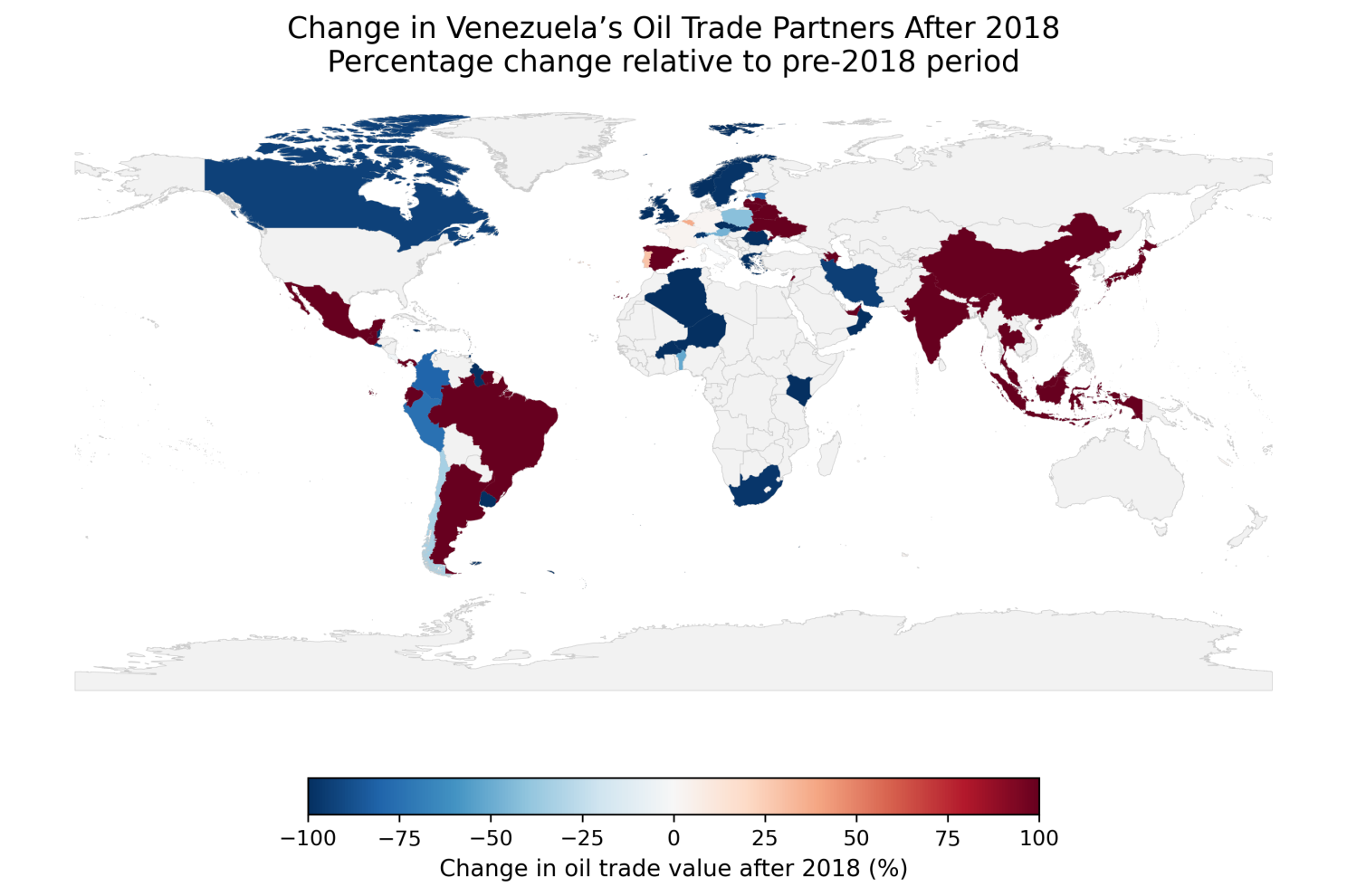

Before 2018, Venezuela’s oil trade was highly centralised around a small group of large buyers, most notably the United States and several Atlantic-facing partners. The United States imported $13 billion worth of oil, with Colombia a distant second at $0.57 billion, according to UN Comtrade data.

After the 2018 break, recovery has taken place through diversification rather than replacement. The United States remains the largest partner, but at a much lower level of $3.1 billion. India has emerged as the second-largest destination with $0.98 billion. Exports to China, Türkiye and the United Arab Emirates have also increased sharply.

“In a worst-case scenario, up to half a million barrels per day of Venezuelan oil exports could disappear,” Rasmussen said, adding that “it is far from certain that this will actually happen.”

“Even under normal conditions, a disruption of this size is manageable for the market,” he explained. “In particular, forecasts point to a clear oversupply in the first quarter, driven by seasonally weak demand and OPEC+ production increases.”

Venezuela’s Crude Oil Is Heavy

Another factor limiting higher Venezuelan oil production is the quality of its crude. The country produces a very heavy and sulphur-rich crude oil, which not all global refineries can process.

“Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt is, on the one hand, a geological marvel but, commercially, a serious problem,” said Cyril Widdershoven, a geopolitical strategist focused on energy markets. “A large share of its output is heavy to extra-heavy crude that often requires blending with lighter hydrocarbons.”

He also noted that “due to factors such as sanctions restrictions, tighter shipping insurance, and traders’ fear of secondary exposure, these barrels are stranded rather than discounted” at present. The country’s crude oil system is not only under-funded but also poorly connected to wider markets.

Widdershoven added that Venezuela’s oil industry is capital-intensive. Any Orinoco production at scale requires steady investment in field operations, including steam and diluent supply chains, as well as critical infrastructure. In addition, Orinoco crude operations need upgraders that convert extra-heavy crude into synthetic crude suitable for a wider range of refineries.

“The main question now is why the media and politicians are still using the ‘war for oil’ narrative if oil is not the near-term payoff,” Widdershoven said. “For Trump and others, it appears that access and control could solve high prices. That view is wrong. This is no longer the oil market of the Iraq era. At the same time, largely due to shale oil and renewables, the US is not energy-starved in the same way.”

- Why Oil Prices Are Falling? Brent and WTI Slip after Maduro Capture in Venezuela as Gold Surges

- Middle East Tensions: Oil and Gold Jump after Israel Strikes Iran

- Oil Hits 7-Year High. Should We Brace for a Steep Decline?

Industry Recovery Will Be Challenging

Ivan Sandrea, founder and CEO of Westlawn Americas Offshore, believes the recovery of Venezuela’s oil industry will depend on four factors:

The type of government transition

Willingness of existing in-country players to invest in the short term

Macro conditions

Execution of a structural reset to reposition the oil and gas industry

According to him, Venezuelan oil production from the current base level could be:

• 0.85–1.0 mbd: status quo / low output

• 1.1–1.3 mbd: operational stabilisation (incremental repairs) – 12 to 18 months

• Around 2.0 mbd: pre-sanctions recovery (stage one repair spending) – 24 to 36 months

• Around 2.5 mbd sustained: structural reset with major spending; offshore adds longer-term upside

Depending on the type of transition, production could still fall to between 0 and 0.5 mbd before recovering. A transition that supports existing leaders would only delay any recovery.

“For shipping and energy markets, the main issue in the coming period will be risk premium,” Widdershoven added. “Any military escalation in an oil-producing state directly affects global supply risks. This remains the case even if the volumes involved are not large at first. US actions have added uncertainty around sanctions and disrupted trade flows. If this situation leads to long-term instability, those limits will become firmer.”