Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi

Oil prices jumped after King Abdullah’s death Friday morning. But experts assert Volatility will subside and pin the absolute floor at $40 a barrel.

BNP Paribas’ senior oil strategist agrees that the new King Salman “was already involved in policy making prior to the passing of the king,” so almost certainly “he’ll maintain [Abdullah’s] agenda.”

But it is oil minister Ali al-Naimi, himself nearing 80, that has charted oil policy since 1995. Now he no longer shares the close association he had with the late king. King Salman has assured that Naimi will stay on at least until volatility subsides, but what happens after?

With enough royal uncertainty to thrill George R. R. Martin, it’s important to understand Saudi reasoning if we’re going to predict future volatility. Why is Naimi refusing to prop up prices even after a 60% decline? Will his eventual successor do the same?

Cold War, Hot Tempers

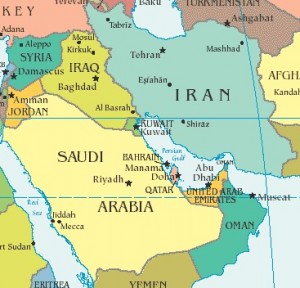

One popular theory—and popular to debunk—is that the US is cajoling Saudi Arabia (who controls 15% of world oil reserves) into weakening Russia. This harkens back to the fall of the Soviet Union, which can be traced to one fateful day in '85 when the Saudis stopped protecting oil prices. The Soviet Union experienced export revenue losses until their economy stalled completely in ‘89.

Some credit Reagan, but that’s conjecture. Leaving the “black oil” conspiracy theories to the X-Files, there are many public records detailing factors within OPEC that led to the Saudi decision, such as other members cheating on agreed quotas.

Similarly, Cold War politics are likely the last thing on Saudi Arabia’s mind today. As is punishment over Russia’s role in supporting Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. Saudi Arabia already made clear its objection when it snubbed a seat on the UN Security Council.

Besides, if their aim was political, they would be proclaiming it like they did during the 1973-74 Israeli oil embargo. Saudi decision making is almost certainly linked to neither the crisis in Ukraine nor the crisis in Syria.

Persiana Non Grata

Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani recently threatened that Saudi Arabia will suffer just as much as Iran from falling oil prices, if not more. And he’s not wrong. Estimates put 80% of Saudi Arabia’s budget as being dependent on oil. However, the Saudis, with hundreds of billions in foreign Exchange reserves, can suffer through bottom-floor oil prices for at least several years.

Rouhani’s denouncement is the latest in a series of Iranian protests. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, has also gone on the offensive, accusing Saudi Arabia of using oil as a political weapon. It’s a popular theory, actually.

Many think Saudi Arabia is trying to weaken Iran, especially at the nuclear negotiating table, believing that the Saudi arch-nemesis is getting too much flexibility from world powers.

Since roughly one-third of Iran’s economy is dependent on oil exports, and given the economic sanctions already in place, the drop in oil is definitely adding to their economic woes. Iran and Venezuela have vowed to work together to stabilize falling prices.

But it’s doubtful that Saudi Arabia’s oil policy centres on Iran—squeezed well enough already without a Saudi oil kamikaze attack. Naimi spelled this out, “There is no effort against anyone in the international oil market, there are no conspiracies against other countries.”

American Revolution

With the US shale revolution having nearly doubled American output (to nine million barrels a day), another popular theory is that a fearful Saudi Arabia is trying to lower oil prices so that US entrants will be forced out of business (shale extraction being more expensive than traditional methods).

Naturally Burning Oil Shale

But the Saudi kingdom has quelled revolutions more worrying than shale. On the contrary, Saudi officials have been heard calling shale a blessing. How come? The truth is probably somewhere in the middle.

Too low of a price will, indeed, force many US entrants out—naturally propping up oil prices. Likewise, shale producers can ramp up production if prices rise. So a likely scenario is that the Saudis, fed up with playing the role of “swing supplier” are counting on shale producers to take their place.

Conversely, if Saudi Arabia were to cut back now, there would be nothing stopping shale oil producers and other non-OPEC members from eating up that market share. This explains Naimi’s comment, “We are going to continue to produce what we are producing [and to] welcome additional production if customers ask for it... If [other countries] want to cut production they are welcome… certainly Saudi Arabia isn’t going to cut. [That] position we will hold forever, not [just] 2015.”

Sheikh’s New Thawb

Another fear at the forefront of Saudi decision making is the situation that developed at the end of 2008, when OPEC cut oil production to buoy prices, but the economic downturn kept prices falling. A repeat of that scenario is just as likely to occur today, since the global economy is uncertain at best.

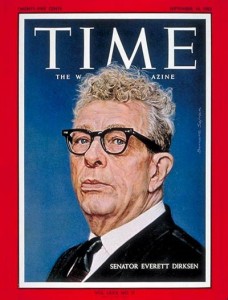

“The oil can is mightier than the sword,” US Republican Senator Everett Dirksen once said in 1965. So astute was this quote that it made The New York Times Magazine cover that March, and Dirksen with it (albeit after having already made the cover of Time twice).

I like to imagine that Naimi has a framed copy of that New York Times issue hanging somewhere in his offices. And in times like these, I like to imagine that he looks at it, straightens his back and lifts up his chin—quashing the fear that, these days, his “sword” might be as useful as a decorative scimitar.

What to Watch?

So the biggest factor to pay attention to is overall global demand. Saudi Arabia will keep producing as long as the demand is there. Smaller oil producer will have no choice but to be dragged along. Seeing as it's not based on political power plays, and for fear of a repeat of 2008, I don’t imagine any incumbent oil minister (all signs pointing to Khalid al-Falih) will go against Naimi’s internally respected judgement.

Once oil falls below a certain threshold, expect shale oil entrants and others to start exiting the market (some oilfields already signalling cutbacks). This will serve to prop up the price until equilibrium is reached. Wall Street might very well be correct in predicting this price to be around $40 a barrel.