A significant proportion of retail brokers and prime of primes deliberately internalise the majority of client flow. This is not a weakness or a temporary compromise. It is a rational commercial choice.

For many firms, B-booking works. Client behaviour is statistically favourable, flow nets naturally, and internalisation delivers cleaner economics than externalising every trade. In stable market conditions, the model is efficient, scalable, and predictable.

The problem is not internalisation.

The problem appears when internalisation stops working and risk must be released into the market. That moment almost always coincides with deteriorating liquidity , widening spreads, and heightened volatility . The cost is not linear. It accelerates.

Delayed hedging and threshold-based controls, which are common in B-book dominant models, quietly introduce non-linear loss. Not because the strategy is flawed, but because the timing and structure of its controls are fragile under stress.

Internalisation Changes the Shape of Risk

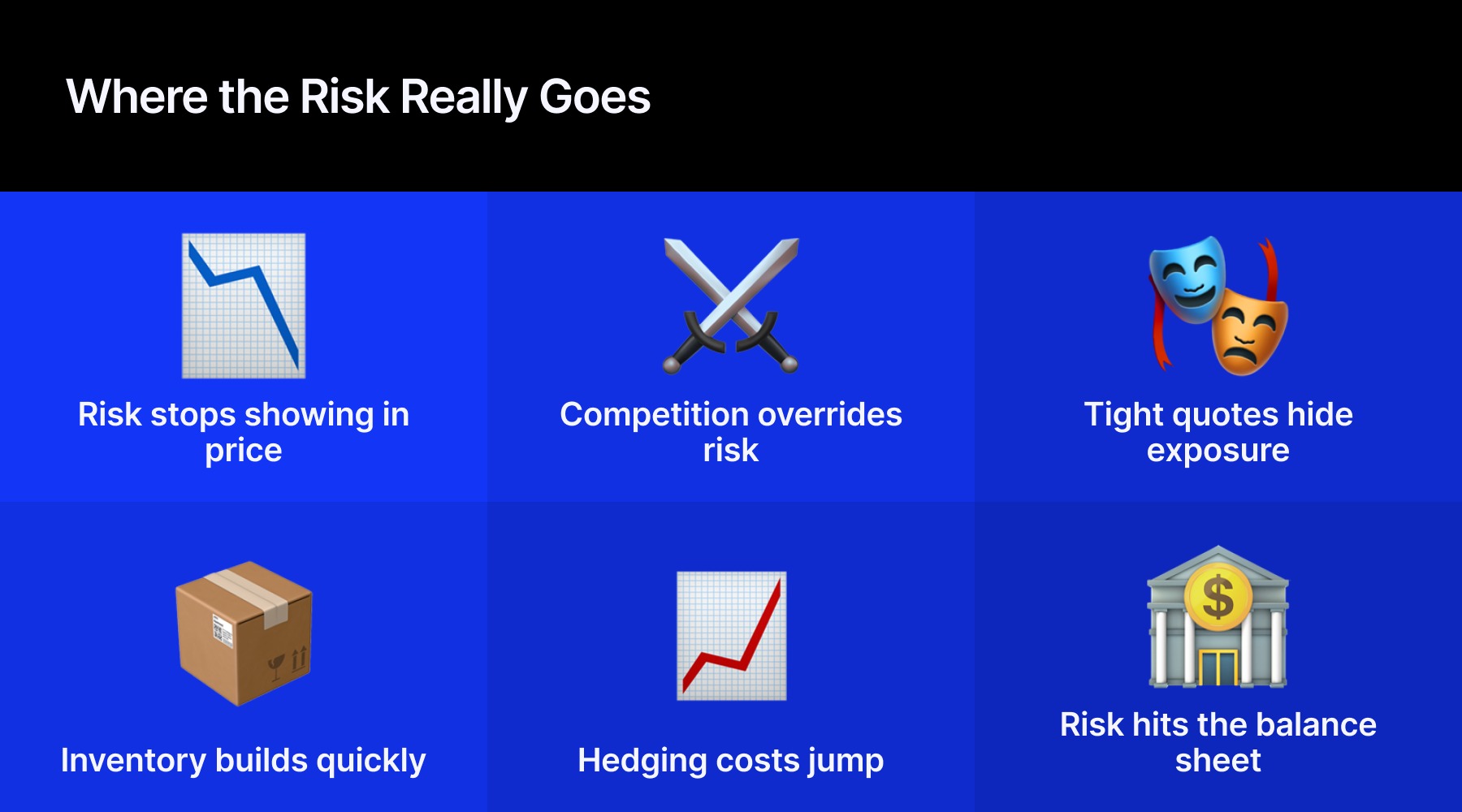

B-booking is often described as reducing risk. In practice, it redistributes it.

Instead of paying spread continuously through immediate hedging, the broker accumulates inventory and relies on netting, client asymmetry, and time diversification. As long as exposure builds gradually and markets remain liquid, this works well.

However, internalisation postpones market interaction. Once the decision is made to hedge, the broker is no longer acting opportunistically. They are acting under constraint.

The difference between those two states is subtle in calm markets and decisive in fast ones.

Where Delayed Hedging Really Comes From

In most retail and hybrid models, delayed hedging is not caused by technology. It is caused by design.

Typical controls include exposure bands within which no hedging occurs, minimum size thresholds, netting windows, volatility or spread filters that suppress hedging, and manual approval gates during fast markets.

Each control makes sense in isolation. Together, they allow risk to accumulate quietly and release it abruptly.

Market stress compresses time and correlation. Exposure builds faster, multiple thresholds are crossed in quick succession, and execution quality deteriorates at the same moment hedging urgency increases.

The hedge arrives later than expected, into a worse market than assumed.

- Razor-Thin Retail Spreads: A Challenge to CFDs Brokers

- B-Booking Is Risky for CFD Prop Firms, but What Is the Alternative?

- B-Book Prime of Primes Are Risky for Brokers, but A-Book Counterparts Are Rare

From Linear Exposure to Convex Loss

Internalisation models are usually calibrated on expected value. Risk limits, thresholds, and hedge cadence are tuned to average flow, average volatility, and average execution cost.

The problem is that losses are not generated at the average. They are generated in the tail.

When exposure is allowed to accumulate inside a band, the broker is implicitly assuming that:

- Exposure grows approximately linearly in time

- Hedge cost is roughly proportional to hedge size

- Execution quality is independent of urgency

None of those assumptions holds in stressed regimes.

Empirically, three relationships break down simultaneously.

Exposure growth accelerates: Client flow becomes clustered and directional. Net exposure often grows super-linearly with volatility. What takes hours to accumulate in calm markets can occur in minutes when volatility doubles.

Hedge cost becomes convex: Execution cost is no longer a linear function of size. Spread paid, slippage, and reject probability all increase as a function of urgency and market stress. The cost curve steepens precisely when the hedge is most needed.

Delay increases conditional loss: The expected cost of hedging becomes path-dependent. Two identical exposures can have very different realised costs depending on whether the hedge is initiated before or after a volatility regime shift.

The result is that a control system designed to manage linear risk is suddenly exposed to convex outcomes.

Thresholds as a Short-Volatility Position

A threshold-based hedging rule can be expressed simply as carrying risk until the price moves far enough to justify paying the spread.

This framing reveals the embedded optionality.

Inside the threshold, the broker collects economic benefit by avoiding hedge costs. Once the threshold is breached, the broker pays the full cost of hedging under prevailing conditions.

In effect, the broker is short a volatility-dependent option whose payoff is realised when the threshold is crossed.

Most days, this option expires worthless. On a small number of days, the payoff is large and negative.

Quantitatively, this shows up as:

- Low variance in daily P&L.

- Fat-tailed loss distributions,

- Benign average slippage metrics.

- Extreme slippage and reject clustering in the top few percentiles of events.

This is why average execution statistics are poor indicators of true risk.

When Holding Risk Feels Optimal, but Isn’t

Many internalisation models are explicitly designed to hold risk. The rationale is straightforward: client flow mean-reverts, time nets exposure, and releasing risk too early incurs unnecessary spread and slippage.

In stable regimes, this logic is often correct.

The issue is not that holding risk is irrational. It is that the decision is usually justified using expected value, while the cost of holding risk is realised through variance and tail events.

When a broker chooses to hold inventory rather than release it, they are implicitly assuming that:

- Future client flow will offset current exposure

- Market conditions will remain sufficiently liquid

- Execution cost tomorrow will be no worse than execution cost today

Those assumptions hold most of the time. They fail together.

From a risk perspective, holding inventory is not free. It is a position with a time-dependent cost of exit. The longer the position is held, the more its exit cost becomes conditional on the regime.

What appears to be patience can, in stressed markets, become an unpriced option written to volatility.

Why Delay Multiplies Loss, Not Just Cost

The economic impact of delayed hedging is often described as “a bit more slippage”. In practice, delay multiplies loss through interaction effects.

Three measurable variables matter:

- Δt: time between exposure creation and hedge completion

- σ: realised volatility during that window

- C: execution cost per unit hedged

A simple way to formalise the effect is to split the cost of delay into two components:

Total Cost ≈ (Exposure × Price Move while waiting) + (Hedge Size × Execution Cost)

The first term captures the price movement incurred while risk is carried. It increases with the length of the delay and with realised volatility during that window. The second term captures the execution penalty paid when the hedge is finally placed. That cost is not constant. It rises with urgency as spreads widen, available size fragments, and reject rates increase.

In calm conditions, execution cost is relatively flat with respect to both time and volatility.

In stressed conditions, execution cost becomes a convex function of both.

That means:

- Increasing the delay by a factor of two can increase the total cost by more than a factor of two

- Identical hedge sizes can produce materially different outcomes depending on timing

- Delaying hedging into a higher-volatility regime increases both price risk and execution risk simultaneously

Loss is no longer exposure multiplied by market move. It becomes exposure multiplied by market move, multiplied again by an execution penalty.

This is the non-linearity most control systems fail to capture.

XAU/USD as a Stress Amplifier, Not a Special Case

These dynamics exist in major FX pairs, but they are easier to observe in XAU/USD because the slopes are steeper.

In gold, the relationship between volatility and execution cost is stronger. Spreads widen more abruptly, available size collapses faster, and reject rates increase earlier in the volatility cycle.

This means the gradient of execution cost with respect to delay is higher.

In practical terms, a one-minute delay in a fast gold market can be economically equivalent to a much longer delay in a major FX pair. The same control logic, therefore, produces visibly worse outcomes sooner.

XAU/USD does not introduce a new risk. It exposes the same risk with a higher signal-to-noise.

Read more: Silver and Gold Price Surges Force CME to Change How It Calculates Precious Metal Margins

Measuring the Problem Properly

To ground this analysis operationally, the metrics are simple and powerful.

Measure distributions, not averages, for:

- Time-to-hedge conditional on volatility regime.

- Execution cost as a function of hedge urgency.

- Reject probability versus hedge size and spread state.

- Exposure growth rate before threshold breach.

- Tail P&L contribution from the top 1 to 5 per cent of events.

When plotted correctly, most firms see the same pattern: stable averages, unstable tails.

That is not a market failure. It is a control design issue.

Designing Controls that Survive Stress

The objective is not to abandon B-booking. It is to remove brittle behaviour.

Practically, that means:

- Progressive or proportional hedging rather than binary triggers.

- Volatility-aware exposure bands that tighten as regimes change.

- Separating risk release from execution-quality gating.

- Pre-authorised stress playbooks that remove decision latency.

- Stress-testing the control system itself, not just the book.

These approaches preserve internalisation economics while materially reducing convex loss.

Reframed Quantitatively

Internalisation optimises expected value. Risk management must control variance and tail loss.

Delayed hedging shifts cost from the mean into the tail. Thresholds compress that tail into a small number of extreme events. Volatility turns those events into convex losses.

The firms that manage this well do not predict markets better. They design controls whose cost curves remain shallow as volatility rises.

Because once the hedge becomes urgent, the mathematics are no longer on your side.